What comes after wokeness?

It's tribalism with a twist; protection rackets and content machines.

The political Left and Right could, once upon a time, be distinguished by their pathologies. You could think of the Right as a cranky old man (stuck in his ways, paranoid about challenges to his authority, nostalgic, melancholic…) and the Left as an annoying adolescent (impatient, irresponsible, narcissistic, needlessly destructive…). But political ideologies and accompanying coordinates have become increasingly scrambled. Hysterical denunciations, callous disregard for free speech, infantile attitudes to authority – hallmarks of the Left’s degeneration over the past few decades – are now all hallmarks of the Right too.

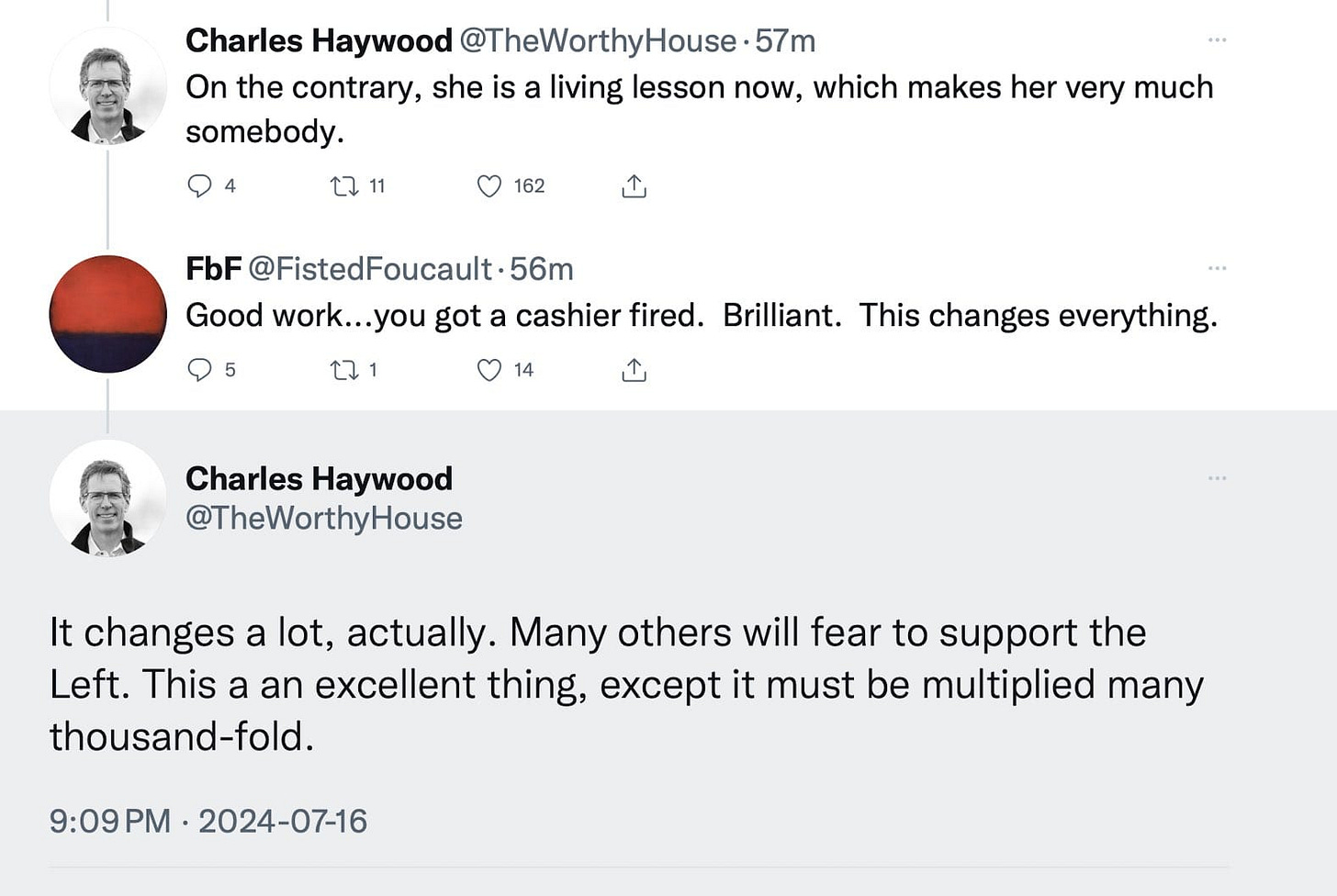

You may have noticed that some on the Right have been exhibiting woke-envy. That is, they observe the Left “getting away with it” and want a piece of the action. In one notable (viral) recent case, US conservatives tried to get a random Home Depot worker fired for badspeak. Specifically, Chaya Raichik, the woman behind the “Libs of TikTok” social media accounts (3.3M followers on X alone), successfully drew the retailer’s attention to one of its workers having posted "To [sic] bad they weren't a better shooter!!!!!" on Facebook, in response to the attempted assassination of Donald Trump. This resulted in said worker’s sacking.

Some justified this blatant act of cancel culture as righteous revenge. It probably was. But if so, we shouldn’t take conservative claims to stand against cancel culture very seriously.

In a wider sense, however, what seems to be happening is a sort of mimesis, a concept popularised by the late French Catholic scholar René Girard. According to his psychologistic theory, our desires operate according to a triangular structure – basically, you desire the object that is the object of the other’s desire; our desire is mediated by a third party. Think of the way a child only wants to play with the toy that his peer currently is playing with. Girard’s theories have become increasingly popular on the Right (a good explainer here) for what I gather are two main reasons: among those who are secular and ‘muscular’ (interested in power, competition, etc) it is because Girard explains and (for them) justifies group rivalry. It’s a sad and nihilistic worldview with no higher goods, just dog eat dog (or rather: dog eat chew-toy of other dog). Girard also appeals to religious conservatives: rivalry creates the need for scapegoats as a way of releasing social tensions; Christianity subverts that scapegoating function through the violent crucifixion of an innocent (Jesus Christ).

Ironically, or maybe fittingly, Girardian mimesis can explain the Right’s adoption of the full suite of woke practices introduced by the Left. At least, Girardian mimesis without the Jesus/redemption stuff.

Through the so-called “Great Awokening” of the past 13 or so years, the liberal-left has adopted “a style of political interpretation” that “filters all problems through the matrix of identity, views identity-related issues as always systemic, and assumes said problems can only be solved through institutional upheaval and identity-based bureaucratic counter-measures.” Maybe the appeal of such a style was too much to resist for the contemporary Right. The attention from institutions that identity-political claims receive become an object of mimetic desire for the Right. So now the same infantile attitude to authority pervades the political spectrum: everone displays an ostensibly punky anti-establishment or anti-authority stance, which also repeatedly calls on authority for recognition and restitution. "Acknowledge me as a victim, and rearrange bureaucratic processes to account for this recognition.”

Understood as such, wokeness becomes the “emerging bipartisan consensus”, as Tyler Austin Harper has put it in a recent piece in The Atlantic. As Harper suggests, wokeness is content-neutral and ideologically plastic, but is unified by “a suite of rhetorical strategies – safety panics, the relabeling of emotional discomfort as ‘violence,’ and of course, stifling speech in the name increasing safety and combating violence.” One can see how this plays out in the hands of the dissident or alt-right: those of little melanin, or white men in particular, are being discriminated against by corporations and the state – institutions in the hands of woke multicultural elites – and so must be protected.

I don’t want to get hung up on the definition of wokeness or whether wokeness is the correct term to describe the victim-identity politics on the Right (for what it’s worth, I’ll venture my own at the end of this post). What I want to focus on is the following chain of signification:

< victimhood - identity - the market - authority >

I would like to know why it is that political claims seem only to advance on the basis of prostituting one’s victimhood, and why that victimhood is usually a collective one (“I belong to victimised group”), precisely at a point in history in which we have never been so atomised.

The sociologist Eva Illouz, whom I spoke with for a recent Bungacast episode, points us in the right direction. We live in a society in which the only authority is the market; it is competitive, and this “dull compulsion”, as Marx called it in reference to economic relations, engages us all, in areas well beyond the formally ‘economic’. As such interests and instrumental rationality (treating people as means not ends, etc) pervade these interactions. The claim to be a victim may be a neutral fact. We may simply have been the object of an assault or an injustice. The problem is that we suspect that in “presenting oneself as the victim of an assault”, we are “enjoying it: enjoying the attention, enjoying the recognition, enjoying the compassion, enjoying the pity.”

Illouz continues: “…when we say ‘victimhood’, we are already not fully compassionate with the victim. And we are not fully compassionate, I think, because we suspect there is something that the victim is actually enjoying in putting herself in the position of a victim.” The reason is explained in this clip below: we suspect the victim to be pushing forward their own interests, because that’s what we do in market society.

This instrumental victimhood is then a way of enclosing oneself in a fixed identity: you aren’t letting go of your victimhood, you continue to live in it, and to prostitute it. Illouz continues this line of reasoning:

“I think the reason why there is there are so many problems with victimhood is it is too strong of a boundary marker between you and the Other, and that it really creates antagonism in the social bond as opposed to creating mechanism, for example, either of healing or of forgetting – because I think victimhood is about memory and it is about woundedness, and the memory of woundedness. And constantly rehashing and rehearsing the wound to the point where when it becomes too often rehearsed, it becomes suspect of no longer being connected to a real experience, which is, I think, the moment we are living in right now.”

The dull compulsion of identitarian competition means that, once the Left became woke, there was a good chance the Right would eventually as well. And with every other identity group represented (in the sense of “standing for”, not “acting for”), then someone eventually would seek to speak for straight white men, as straight white men. And this competitive logic applies to rhetoric and discoursive modes too. You wouldn’t bring a (tolerant and open debate) knife to a (cancel culture) gun fight.

This is especially so because both sides in the culture war are in denial of their own status and position. Neither represents masses of people, both represent fragments of the middle class. The Left is the party of the university-education professional; the Right is the party of small business owners. Both compete for patronage from the oligarchy, but both frame their appeal in populist mode, to the “marginalised”. They just speak to different groups.

But why don’t they just say what they are and declare their interests brazenly? “We defend the interests of professionals and their right to apartments and good schools in nice urban districts, plus recognition and status for doing jobs that require higher education!” That’s what liberal centre-left politicians could say. But they won’t, because it’s a losing proposition if you want something close to an electoral majority. And this is especially so in the US and the UK, where the electoral systems don’t provide for existence of minority parties like continental-European multiparty parliamentary systems.

If you think this last point to be irrelevant, consider how much of identity politics across the West has as its origin the electoral exigencies of one single party, in one single country: the US Democrats, and their need to cobble together a “rainbow coalition”, appealing to different “marginalised” groups on identitarian grounds, after losing the working class. That set the pattern decades ago, and if we forget it, it is only because this mode of politics has become standard across the West.

Beyond that, the non-declaration of interests can also be tied to fact we live in societies in which the naked declaration of interest remains taboo. Visions of the Good Life or the Good Society are also pretty scarce. Political rhetoric is thus dominated primarily by fear-mongering, or else by claims of injustice on identitarian grounds. And often both. Liberals are helping immigrants steal your job and perverts to interfere with your children. Conservatives are fascists who will oppress brown people – and if you don’t care that’s because you benefit from white privilege. Everyone joins in the Oppression Olympics and tries to sell their victim-identity in the market of public opinion. Or you pose as a protector of a victim-identity. Either way, it bespeaks of a politics and society stuck in an eternal present: there are no proposals of how to reform or transform society, just bitchy litigation on the terms of the current rules.

“OK, but didn’t wokeness peak in 2022?,” you ask. Indeed, many people are saying this. (These are examples chosen almost at random: some I’ve read, others I haven’t, but, my word, does searching “peak wokeness 2022” throw up a lot of hits!). And if search-engine hits don’t convince you, how about the publishing industry’s Owl of Minerva? Plenty of serious critiques of wokeness are now coming out, some that I anticipate more eagerly than others. In fact, if Dustin Guastella’s sharp review is anything to go by, we can add this one by Susan Neiman to the pile too.

My suspicion, for what it’s worth, is as follows: the public has tired of wokeness as a rhetorical strategy (most hated it all along); politicians therefore see decreasing gain to be had from it; and institutions will eventually slough some ‘woke’ practices off, but most are slow-moving bureaucracies so it will take a while. And particularly in the case of academia, NGOs, and large parts of the public bureaucracy, these are dominated by the hard-core of woke centrists, because these are the people that gain most from administering the system of identitarian rewards and censorious punishments. So it will be a long process.

But nevertheless, “woke” will seem less present in the Discourse, and will be less obviously coded as “progressive”. But if there is indeed a generalisation underway of the worldview and practices that we call ‘woke’ – that is, identitarianism and cancellation, to put it in a nutshell, then it simultaneously becomes the common basis for “politics”. And by politics I mean group competition and claims-making in regard to public authority, for redistribution and recognition (but really, I mean the latter).

This is likely to be very ugly, Guastella suggests:

As bad as wokeness is, what’s next could always be worse. If Foucauldian-Schmittianism wrought havoc on the Left, this “mind virus” is likely to cause even more trouble if its tenets become widely adopted on the Right. Consider that the major impulse of wokeness was a kind of reflexive pity for victims. Often, this pity was misplaced, and real economic victims (like poor white men) were scapegoated as the holders of privilege by well-heeled activists.

Yet the “victimology” mindset can go both ways. If the woke have insisted that characteristics like a person’s skin color, or their gender, or whatever else, marks them as fundamentally different in a grand metaphysical way and have made that point central to political appeals, then what happens if the Right takes up the charge by simply reversing the friend-enemy polarity? They will say to young men that their loneliness is not a function of “toxic masculinity” but instead the result of women’s claims to equality. And they will say to poor whites, who are adrift and frustrated, that they don’t need to “abolish ‘whiteness’” — instead, they should embrace it. We already see this beginning to happen — a reversal of the Left’s hard-fought victory in the civil rights era.

The era of “progressive neoliberalism” has seen definite advances in rolling back racism and sexism, but it has come at the “cost” of massive economic inequality, as Kenan Malik, Adolph Reed and Walter Benn Michals, and others have argued. (Or to put it more accurately: the loosening of race-and-gender-based authority came after the defeat of the organised working class. The new, socially liberal order advanced by your Clintons and Blairs suggested a different model of legitimation, one which would replace the more traditional, conservative appeal mobilised by Reagan and Thatcher as they mounted their neoliberal assault). But wokeness is not to be equated with social liberalism as such. It doesn’t say “be tolerant, don’t discriminate”, it says, “recognise race/gender… and if you don’t you’re cancelled”. This reifies race and gender. In the woke phase of neoliberalism, we are more fragmented and atomised than ever, more stuck in our identities. And the cruellest irony is that race returns, in the form of "right-wing wokeness" – the particularist victim politics of the Right, in defence of put-upon and neglected “whites.” And of course those on the woke Left will take this as evidence they were justified in shouting that the Right and those that vote for them are all racist bigots.

So does this mean generalised ethnic conflict? Guastella seems to endorse Neiman’s understanding that generalised wokeness equals tribalism. As he writes, “to be woke is to hold a tribal worldview, one that says that the in-group (defined by skin color, or gender, or nationality, or indeed even those who identify as “progressive”) is ‘good’ and the out-group is ‘bad.’” Nazi jurist Carl Schmitt famously thought that’s what politics basically was: “the specific political distinction to which political actions and motives can be reduced is that between friend and enemy.” Schmitt was wrong: politics can be much more than that, and struggles waged in pursuit of a common good, on a universalistic basis, have existed and succeeded; and hopefully will again.

But politics bereft of the civilising force of the rising bourgeoisie and of the organised proletariat probably does devolve into historically meaningless inter-group struggles for power, often on ethnic bases. As critical theorist Max Horkheimer noted in a fragment from the early 1940s called “Rackets and Spirit”: “The basic form of domination is the racket […] The most general functional category exercised by the group is protection.” Horkheimer suggested this was in some way the natural state of public struggles for power. (I remember thinking this was a neat reading of the fragmentary Frankfurtian theory through mob films and Trump but I haven’t re-read it to check).

Horkheimer’s collaborator, Theodor Adorno, mischievously, darkly, took things further, penning a pastiche of lines from the Communist Manifesto:

In the image of the latest economic phase, history is the history of monopolies. In the image of the manifest act of usurpation that is practiced nowadays by the leaders of capital and labor acting in consort, it is the history of gang wars and rackets.

Are protection rackets the motor of history? Was liberal capitalism just a historically brief interlude? We now find ourselves without competition between universalising ideologies – or lacking at least one party to the struggle raising a universalist banner – and instead are increasingly faced with competition on identitarian grounds. Are we sliding backwards into tribal conflict?

Well, not quite. Western societies have not yet become Lebanon – a country that can trace its inertia, stagnation and growing disorder to a dysfunctional and ossified confessional system. There, society is organised vertically, by ethnic allegiance, rather than horizontally by class; “a small politically connected elite appropriates the bulk of economic surplus and redistributes it through communal clientelism.” (It is worth comparing the political and social economy of this arrangement with that which obtains in Western societies. I can recommend Rima Majed’s analysis here, or listen to my interview with her.)

As things stand, the victim-identity nexus, fuelled by acts of censorship – that is, “wokeness” – has not yet become a matter of redistribution of economic goods and of public office. Not Lebanon-style anyway. It is not formalised and is still the object of democratic, discursive competition (“vote for Kamala cos she’s a black woman” and not “Kamala will be the next president because the office has been reserved for a black woman”; Hilary tried that and it didn’t work).

So, for all that identity-based clientelism may be growing in the West, there are counter-tendencies. Staying with US politics, we see the Republicans gaining ever-larger shares of black and hispanic voters. This should be met with equanimity, even welcomed, insofar as it breaks the Democrats’ identitarian logic, and thus the bipartisan logic of the wokeness machine.

Instead, and by way of oblique conclusion, it seems to me the more pertinent features in describing how post-ideological (but hyperpolitical) politics functions in the West today cannot be boiled down to tribalism. Yes, there is at base competition, and competition often organised collectively on nothing so much as friend/enemy distinctions. But we must also add the following:

Hypermedia, where claims, images, symbols are sent in every direction.

The Content Machine™️, where ideas are recombined in any fashion, irrespective of valid grounds or truth. It's an interminable washing machine in which everything can be laundered into anything else. Meaning is fungible and everything rests on the Content Machine's say-so.

A narcissistic culture where your feelings, not your ideas or interests, are paramount; where you look for affirmation or indulgence from authority for those feelings; where politics is meant to be about you.

A society in which authority is in denial of itself; where the consumer is king and no one in a position of power truly assumes their role; where elites do not seek to rule and everyone pretends to be the little guy – that is, either the hustler or the trauma-sufferer, and often both.

This all gets layered onto a state of low growth, little new value production, and hyper concentration of the social surplus in a few hands. Tensions escalate, as there’s not that much extra to throw around. Often, because of an absence of political representation, economic difficulties get parlayed into cultural resentments and group competition.

This all gets analysed by politics-knowers who continue to think and speak in modern (that is to say, outdated) term: left and right, progressive and conservative, socialist/Marxist and fascist. But these words have little connection to past traditions. This obscures, not clarifies, what is going on; and has the unfortunate consequence of deepening the culture wars, not breaking us out. I suspect that is what many of these politics-knowers actually want.

Later, I’ll write more about culture war. And how it relates to “techno-populism” – the way all flavours of politics today are simultaneously technocratic and populist. But really, these are all just different ways of describing how the contending “sides” resemble one another. Right-populists or national-conservatives have become part of the furniture, they’re “on the carousel” of alternating in and out of government (as my friend and podmate Philip Cunliffe prefers to put it). They are Her Majesty’s Loyal Opposition. The generalisation of wokeness only deepens my conviction in that diagnosis.

Briefly, on definitions:

There is a radical and an institutional wokeness. I make this distinction because there are critics of wokeness “from the left” whose basic proposition is, “drop the phony corporate HR stuff and do identity-politics harder… on the streets”). I want to emphasise that these are just varities of the same thing. Mom works in Human Resources, Daughter is a member of a Maoist student group.

Wokeness is or has…

a rhetorical style: hysterical, urgent, exaggerated, self-dramatising

an institutional form: corporate and public bureaucracies; managed along the lines of human-resource depts, in which firing and/or public disgrace are the means of “discipline” but conformity is usually achieved at an earlier stage through censorship or its threat

an ideal subject: the victim-crusader

a vision of politics: inter-group conflict (which disguises the reality of individual competition)

philosophically informed by: Nietzsche, Schmitt, Foucault

Your article reminded me of something that's bugged me about this ideological moment for years now. That is, its lax epistemology makes it impressively easy to get theory-quoting leftists to espouse shockingly conservative views, under the guise of listening to xyz voices. Thinking of my own people group, anyone who claims to have the "true" Jewish take on something should certainly not be listened to on anything -- but yet this is what has happened, over and over, in determining how to Solve Oppression.

Excellent piece. It reminded me of Wendy Brown’s classic critique of identity politics in “Wounded Attachments”.

I find that another useful (and compatible) approach to thinking about wokeness is to understand it as moral project. Its aim would be establish strict and enforceable rules and regulations via media and bureaucratic power, as a reaction against secularization and social and moral liberalization (post death-of-God, decline of symbolic efficiency, incredulity toward metanarratives, etc.). Olivier Roy develops that thesis on The Crisis of Culture.