Woke Nazis stole my lunch (the real treason of the intellectuals)

What can Julien Benda's interwar critique of political passions possibly tell us about our bloodless age?

Few people are accused of treason today, rhetorically. At least not with respect to big collectivities like nation and class. But Julien Benda’s formulation, “la trahison des clercs”, has had enduring currency, as various groups and strata – clerks, intellectuals, experts – have been lambasted over the past century for not performing their proper function. In 1999, Edward Said rightly charged the intellectuals with treason over the NATO bombing of the former Yugoslavia. They cheered on the Western military alliance, dressing up imperial war in the language of humanitarian concern.

One must always begin one's resistance at home, against power that as a citizen one can influence; but alas, a fluent nationalism masking itself as patriotism and moral concern has taken over the critical consciousness, which then puts loyalty to one's "nation" before everything. At that point there is only the treason of the intellectuals, and complete moral bankruptcy.

Said was performing his function as an intellectual, and was right in throwing stones. More recently, Niall Ferguson stood as a mortal conduit for the immortal law of Godwin, tasking American academia with failing at “the separation of Wissenschaft from Politik”.

For nearly ten years, rather like Benda, I have marveled at the treason of my fellow intellectuals. I have also witnessed the willingness of trustees, donors, and alumni to tolerate the politicization of American universities by an illiberal coalition of “woke” progressives, adherents of “critical race theory,” and apologists for Islamist extremism.

You see, “exactly the same thing has happened before,” when “the German professoriat had a fatal weakness.” Yes, everything is bad, because of woke. Just like the Nazis.

Lawyers and doctors, all credentialed with university degrees, were substantially overrepresented within the NSDAP, as were university students (then a far narrower section of society than today). To middle-aged lawyers, Hitler was the heir to Bismarck.

This paint-by-the-numbers Weimar-mongering is risible, of course, but Ferguson is at least correct in one observation: “the separation between scholarship and politics has been entirely disregarded at the major American universities in recent years. Instead, our most elite schools have embraced the kind of ‘institutional change’ that [Claudine] Gay has championed.”

The academics have all become activists. Indeed, universities’ pitch to students is often explicitly framed this way, but here and then they get hoist by their own petard. The seats of higher learning find that the students go too far, or pick the wrong causes, as with the pro-Palestine protests. Then Niall Ferguson appears saying, see, this is the problem of (too much) politics. It interferes with the disinterested pursuit of knowledge.

But Ferguson is wrong. He is in one of those typical muddles that purveyors of “non-ideological” thinking get into, which is to presume one can step outside of ideology by simply being practical and evidence-based. This is the biggest ideological conceit of all, because the most deceptive. As a consequence, Ferguson misses the other major “treason of the intelligentsia” today, that which concerns experts.

Most politics and nearly all policy today is justified with reference to scientific expertise, rather than interests or values. There is such a large production of expertise on such a range of issues that practically any political decision can be justified by some bit of research or another. Hence the satirical charge of “policy-based evidence”, in lieu of the technocrats’ vaunted “evidence-based policy”. The prostitution of knowledge has led academia and its supposedly disinterested scholarship to come under the sway of scientism and the technocratic apparatus.

As my friend Ashley Frawley details in a neat piece on “the treason of the experts”:

The imperative to “publish or perish” but also to demonstrate the “impact” of one’s publications has forged an unholy alliance between advocates and policymakers seeking to launder their political views.

Intellectuals are meant to be different, though, they should

…serve as heretics, challenging scientistic orthodoxy and demanding a space for democratic debate unconstrained by the pronouncements of expertise.

But we’ve got a problem, because

…many of those who gain prominence do so because they pose as contrarian experts. They bring you the research and evidence that “they,” the “liberal establishment,” don’t want you to see.

Ashley goes on to cite figures as different as Jordan Peterson and Jonathan Haidt as examples, to drive home the way scientism has colonised critical thought and debate. The ostensible enemies of (mostly liberal, progressive) technocracy are just as wedded to the cult of expertise.

So yes, there has been a betrayal committed by experts, to the notion of expertise. But this is only light treason. The heavy treason is that of the intellectuals, for lacking humility, fear of power and an independent and critical stance.

Those like Ferguson, and the class of people known as centrist dads, only see part of the picture: they react against the academic-as-activist, against wokeness, against hyperpolitics – and hold up the ideal of the post-ideological expert, “untainted” by politics, in its place. They are archetypal sufferers of Neoliberal Order Breakdown Syndrome. They thus do not recognise the role played by the advance of “post-ideology” in undermining both the scholar’s disinterested pursuit of knowledge and the intellectual’s independence and critical stance vis-a-vis power.

To put it bluntly, the decay of contemporary intellectual life looks more like the product of a dearth of mass politics, rather than a surfeit. The main institutional redoubt of the Left is the academy; radicalism is pursued by MANGOs through the institutions. Meanwhile, politics has become “technopopulist”. The activist and the expert have displaced the intellectual.

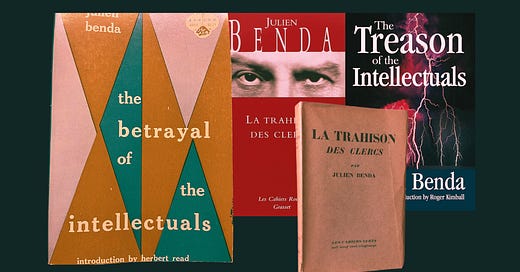

This is a world away from the intellectual scene to which Julien Benda referred to in the mid-1920s, so it would be instructive to mount a comparison, given that the intellectuals are still being accused of treason, even though the crime is different. (I introduced the book at the latest Bungacast Reading Club so what follows is a summary of those remarks and some wider thoughts prompted by our discussion.)

Benda wrote his book from 1924-27, in the shadow of the urkatastrophe of the 20th century, as well as of the Dreyfus Affair before that – a moment which gave the term intellectual wide currency. Émile Zola’s open letter, J’accuse… remains the archetype of a public intellectual’s denunciation of moral and political wrongs. In La trahison…, Benda mounts an opposition to and critique of intellectuals’ adoption and advancement of political passions – of nationalism in particular, but also of the passions of race and of class. For Benda, intellectuals should be disinterested rather than pursue material goods, be universalist rather than particularist, concerned with the eternal or the metaphysical, not the immediate, and exercise reason rather than glorify feeling or will.

I’m using “intellectuals” in English here though Benda’s term in French is clercs, which is etymologically related in English to both clerks (like typists) and clerics (like priests). The US geographer Joel Kotkin has recently revived the latter usage in the form of the clerisy, a term originally used by Samuel Coleridge in the 1830s to describe religious orders. Kotkin’s new clerisy. Here’s what we had to say about the clerisy in The End of the End of History:

Kotkin draws our attention to the ideological role it plays. Found in public and quasi-public institutions such as universities, the media, NGOs and the state bureaucracy, its main function is not economic production but production of culture and morals. The new clerisy is generally favorable to the state, accepting of higher taxes and regulation. According to Michael Lind, this stratum accounts for maybe 15 percent of society today in the US. For Kotkin, it has no structural antagonism with the oligarchy, because it is the latter who fund their NGOs, universities and so on.

This new clerisy would seem to be engaged in both the practices of expertise and of activism. Benda’s ideal of the clerk is the opposite. The clerk is they whose activity is not geared to practical ends but to art, science or metaphysical speculation – the possession of a non-temporal good. “My kingdom is not of this world,” they declare. The clerk maintained opposition to the “realism” of the multitudes (here “realism” means practical and immediate concerns and interests) in a couple of ways:

They were completely removed from political passions, attached to purely disinterested activity (e.g. de Vinci, Malebranche, Goethe); or

They were moralists who preached in name of humanity or justice, in favour of abstract and superior principles, directly opposed to passions (e.g. Erasmus, Kant, Ernest Renan);

Or, when they were engaged, they did so in only an abstract way, still disdaining the immediate (e.g. Rousseau, de Maistre)

Now, Benda acknowledges lay humanity cannot live by the clerk’s rule. There is a division of labour here: clerks have a specific function as moralists. Humanity may do evil, it may stand in hypocritical relation to its proclaimed values, but it cannot be allowed to think it is doing good when it does evil. The clerks need to hold the line.

But, “most of the influential moralists of the past fifty years in Europe, particularly the men of letters in France, call upon mankind to sneer at the Gospel and to read Army Orders.” The clerks no longer keep anyone up at night. At some point as of the 1870s, the intellectuals abandoned their posts and threw their lot in with the realists, making excuses for the exigencies of power; or else they became fervent nationalists, racists, or class warriors. In no small part due to this treason, “our age is indeed the age of the intellectual organization of political hatreds. It will be one of its chief claims to notice in the moral history of humanity…”

Chief among these hatreds is nationalism, which has become cultural, mystical and scientific all at once. Political war now implies war of cultures. “To be a patriot means to defend a particular national form of morality, of intelligence, of sensibility, of literature, of philosophy and of artistic conceptions.” The nation has moreover become the object of quasi-religious adoration. Tying this all together is a notion of historical destiny:

…every one to-day claims that his movement is in line with ‘the development of evolution’ and ‘the profound unrolling of history.’ All these passions of to-day, whether they derive from Marx, from M. Maurras or from Houston Chamberlain [a propounder of scientific racism], have discovered a ‘historical law,’ according to which their movement is merely carrying out the spirit of history and must therefore necessarily triumph, while the opposing party is running counter to this spirit and can enjoy only a transitory triumph.

The scientism of an age very different to ours. National egotism has become a “sacred” egotism: “…political passions are a realism of a particular quality, which is an important element of strength in them: They are divinized realism.” So the two “realist passions” of a drive for material advantages, on the one hand, and for distinction or pride, on the other, are supplemented by this metaphysical passion.

Benda’s errant clerks are guilty of indulging and furthering this worldview, one shared by intellectuals and masses in the interwar period – the highest stage of ideological intensity that mankind traversed. It is almost a wonder that Daniel Bell was able to write only a few decades after, in The End of Ideology, that political ideology had become irrelevant among “sensible” people and now technocratic adjustments to the system were the order of the day. It would be interesting to know what Benda would have made of the technocratic mentality of Bell’s, and our own, age.

One suspects it would also have stood accused of a departure from humanist universalism. For Benda, humanism is a sensitivity to the abstract quality of what it is to be human – it’s an attachment to a concept, which is distinct from humanitarianism, the love for existing human beings in the concrete. And so, the treasonous intellectuals of the 1920s were guilty precisely for denouncing humanism as moral or intellectual degeneration, as evidence of the absence of practical common sense. For “twenty centuries” clerks have argued that “the State should be just”; now they are engaged in practical matters and argue that the State should be strong, and not care about justice. As a consequence, these intellectuals defend arbitrary government, reason of state, and religious attitudes of blind submission, while they denounce institutions based on liberty and discussion.

This vast historical sweep ends up an indictment of modernity and of mass politics as such, and gives Benda a sense of being a man out of time, or a voice from nowhere. This would’ve been so in 1927 as much as now in 2024. We can agree with Benda that it is wrong to follow the monarchist reactionary Charles Maurras in declaring that politics decides morality; and that it is better to follow Plato (morality decides politics) or at least Machiavelli (politics have nothing to do with morality). But the role of intellectual that he envisages – moralist, detached, universalist – was already lost to his age, and we are certainly no closer to recapturing such a Christianity-inflected vision (which is curious as Benda was raised a secular Jew). It is not even clear is such a thing is entirely desirable.

Nevertheless, it may still be useful to stand Benda up against our age. After all, people keep citing him or paraphrasing his denunciation. Though I suspect many do so without really reading him or placing him in context. Benda is a practical tool with which to cast fellow intellectuals as immoral, opportunist scoundrels, which is why so many do it; but they rarely seem interested in grappling with how our intellectual world has changed, or how the wielder of Benda may be guilty of many of the crimes Benda identifies.

The causes for the clerk’s abandonment of disinterested universalism as various: the “imposition of political interests on all men without exception”; the desire or possibility for men of letters to play a political part; the need to play the game of an ever-more anxious class [the bourgeoisie], and the pursuit of fame; the clerks’ adoption of bourgeois vanities; and the decline in knowledge of antiquity and of intellectual discipline. Most of these still apply, some have intensified, others belong to the category “well, that ship has sailed”.

One of Benda’s more interesting foci, in the latter part of the book, is his critique of Nietzscheanism. Some aspects are less relevant today (the idealisation of a warrior aristocracy, the extolling of courage, honour, and harshness, at the expense of pity, charity, benevolence), others more. First amongst these is the cult of success, the idea that “when a will is successful that fact alone gives it a moral value, whereas the will which fails is for that reason alone deserving of contempt.” This lands still today. Then, Benda was thinking of Napoleon, Mazarin and Vauban (both worked under Louis XIV), or Mussolini. In a less historic sense, one can think today of the Peter Thiel zone and the Ubermenschen of Capital, or various theory stars of the postmodern academy.

The second Benda characterises as a decline in reason, from the Cartesian “I think therefore I am” to a contemporary “I am, therefore I think” or “I think, therefore I am not”. The past fifty years (1875-1925), Benda argues, have witnessed the praise of instinct, the unconscious, intuition, and the will, over the intellect. Today’s flight from reason takes a different form, but one worthy of critique in similar terms to that which Benda undertakes. Instead of intellect, abstraction and objectivity, we have the therapeutic ethos and pervasive narcissism.

In sum, we can take from Benda an aspiration to humanism, as an attachment to a concept of what it is to be human, and what humanity might be; a fealty to reason over feeling in public matters; and a critical, independent stance with regard to power.

Benda was a man out of time. The ideal he referred to anteceded the arrival of man man, of mass politics, of mass passions. The descent of the intellectual into the trenches was perhaps unavoidable. Now, mass man has come and gone. The ideological passions are no longer what they were. But we aren’t closer to Benda’s ideal, the conditions do not exist for the detached republic of letters, and it’s unclear whether that would even be desirable. Nevertheless, the space where the pre-20th century intellectual once was is now occupied by the expert-for-sale, or the academic-activist, the bloviator and ass-kisser, the justifier of power and its prerogatives. A 21st century Julien Benda would aim his fire not at nationalism but at commercialism, and at bureaucratic conformity.

What Benda criticised as “realism” – ok for the masses, but not for the intellectuals – has transmuted into cynicism. There is no excess of passion but rather a lack of belief; really, a lack of belief in belief. We tell ourselves we’re smart to it, we’re above it all, we don’t believe in all the bullshit, but yet we continue to participate. Anyone who too-forthrightly denounces the bullshit in the name of a Big Idea draws sniggers, eye-rolling, or at best, a whatchagonnadoaboutit shrug. There is no need for “realism” in Benda’s sense today: the market rules. Instrumental reason predominates. No one needs teaching about how this all works. Equally, we need not be quivering innocents about any of this, nor dupes that fall for any “ideological” justification. But isn’t it a particularly actual sort of naivety that believes “realism” is in need of justification? That we need to meet power halfway? Benda continues to be right on this: principle costs nothing. Better to be a hypocrite than a cynic.