The limits of right-wing anti-managerialism

Can the conservative radicals do social radicals' dirty work for them?

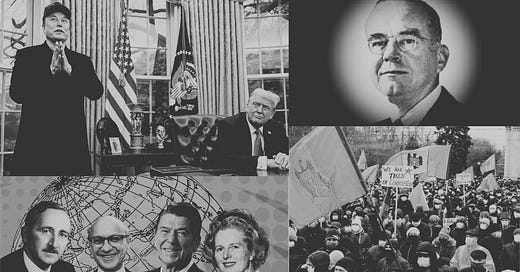

I was sent an essay by NS Lyons in the NYT (thanks Szilárd) that shines a light on der PMC frage – possibly against its own intentions. The essay is worth reading it is own right for neatly putting Burnham’s Managerial Revolution in dialogue with DOGE, Musk, Bannon, Trump. I feel as much a critic of the term ‘PMC’ as I am of the PMC itself. But nevertheless, it is an important debate because it touches very directly on the (dis)organisation of capitalism and political actors and class alliances within and against it.

My case is this: left-wing critics of the PMC might hope that the Right might do its dirty work for it. And this is most likely wrong, for 3 reasons.

1/ The right might talk about how managerialism is anti-democratic, domineering and resists accountability. Moreover it is a dead weight, preventing any social dynamism.

But conservatives are ultimately concerned with culture, values, race. The problem is the wrong managers. In their view, the PMC imposes progressive values on the conservative masses (progressive here meaning variously: woke, statist, scientistic, centralising, future-oriented, socially liberal...)

If a cultural revolution could rip through the managerial classes and a different set of managers be installed, then a lot of the critiques of managerial anti-democracy would subside.

Can conservatives be relied upon to "clean house"? Would a "clean house", from a conservative perspective, generate greater proletarian, or even just plebeian, political autonomy? This is a genuine question though my suspicion is no. Would a genuine “clean house” - an undoing of the managerial revolution – provide space and leverage for radical politics? Possibly, but that’s likely impossible.

2/ The managers are inherently 'progressive'. But this needs unpeeling. The progressivism inheres in scientism, bureaucratic rationality, and centralism. As a consequence, conservative ideas rooted in faith, religion, community, or collectivism are anathema. That may incline managers to a certain basic social liberalism – really a meritocratic individualism.

This does NOT mean managers are inherently woke – in the sense of channelling radical identity politics into bureaucratic form, – nor that they're interested in top-down redistributive policy, nor that they're libertine or any of the other things that primarily concern conservatives.

The first para concern values and practices inherent to managerialism, the second to contingent factors. If the right succeeds in divesting the 'PMC' of the latter aspects of progressivism, they will be content and stop there.

This is because the managerial revolution is necessary to capitalism's advance, it's not an accident or wrong path taken. Conservatives who pine for community and faith, say, but have nothing to say about capitalism, are confused about what they really want and the possibility of getting it.

A Trumpian assault on the PMC won't "go too far", it won't go far enough.

3/ Should we not just cheerlead it, even if it only does part of the job? No.

The nature of politics is that, absent tremendous mass political will, low-hanging fruit will be picked first; the pickers will gorge themselves on sweet nectar and be satisfied.

Conservative anti-managerialism, as we already see, takes on soft targets like universities "not because they are independent bastions of free thought but precisely because they are no more independent than any other managerial institution, staffed by the same class of people with the same interests" – as NS Lyons explains.

The problem is this move would destroy what little good is left of universities: be it basic research or free thought. Moreover, there is a tendency then to institute a right-wing wokeness (all of which underlines point 1 above).

This tendency is well explained here by Greg Conti and Geoff Shullenberger of Compact.

So not only does conservative anti-managerialism not do "our" job for us, it also does a lot of stuff that isn't even desirable, such as destroying professions even further. The good side of the PMC, as Barbara Ehrenreich recognised, was commitments like an ethic of service, professionalism, the pursuit of knowledge etc.

Conservative anti-managerialism does nothing to defend these goods and much to advance their demotion or destruction – particularly in its guise as "right-wing progressivism", carried forth by Silicon Valley.

The end result, in the best-case scenario, is likely to be a renovated managerial elite with more conservative rather than liberal biases; a reduction in some managerial bloat but not enough; and an acceleration in the proletarianisation of the lower professionals.

To conclude:

There is perhaps always something illusory in the radicals' hope that the bourgeoisie might clean its own house. We can see an analogy in the anti-corruption campaigns that have ripped through Latin America or Eastern Europe. They too pretend to renovate capitalism, strip away the anti-democratic chaff, and break clientelistic links between state and oligarchs, and between oligarchs and plebs.

In truth, these are just neoliberal trysts with 'transparency' which merely replicate the hollowing out of democracy on a new level. In anti-corruption, intl capital replaces local capitalists, the state stops cosy deals with the latter and instead restructures itself to serve the former, and the result is society is no more dynamic or free or democratic than before.

Anti-managerialism from the right will make some advances, but will mostly result in a changing of the guard and ultimately a deepening of the anti-democracy it pretends to oppose.

The analogy between anti-managerial and anti-corruption politics as both replicating the hollowing out of democracy is very good, & I might argue that there is also historical sequencing between the two, at least in Eastern Europe:

1. in the beginning (sic!) there was the "actually existing socialism" with its "intellectuals in class power" (in fact: managers and bureaucrats of various sorts) operating a complex (re-)distributive system with strong clientelistic elements. (Important to note here clientelism is always a reciprocal relationship, hierachical BUT reciprocal: political support in exchange for goods&services, as true in the New York and Chicago of Democratic Party bosses as in the industrial towns of Eastern Europe. Reciprocity meaning that there was agency on both sides). This relatively unified and coordinated system was called (somewhat mistakenly) the STATE, operated by STATE-MANAGERS based on an integrative ideology of POLITICAL REDISTRIBUTIONISM

2. then came the anti-corruption drive of the newly emergent Center Right forces (the "regime-changers") which used the anti-clientelistic, anti-corruption rhetoric to break this system: partly the new parties took over the clientelistic networks, partly opened up terrain to Western capitalist firms; all in all creating a fragmented patchwork of competing clientelistic networks and multinational corporations. This fragmented, competitive patchwork was called (somewhat mistekanly) the (economic and political) MARKET, operated by MARKET-MANAGERS based on an integrative ideology of technocratic-managerial TINA.

3. the contradicitions of this system gave rised to the anti-managerial revolution of populism and hyperpolitics, which, on the one hand, attacked the managerial technocracy of old and new, i.e. the remnants of the old socialist bureaucracy+ the operators of competing networks of clientelism + the managers of the new capitalism. On the other hand, it turned political contestation into a spectacle without stakes in material reality; that is to say, they did not fundamentally alter the patchwork described at Point no. 2, the most they did was re-unify the clientelistic networks, rebalance their bargain with multinational capita, and kill the remants of actual expertise among state bureaucracies.

So there is a nice dialectic to it: the redistributive modernist state-politics -> anti-corruption politics -> neoliberal managerialism -> anti-managerial populism all leading to less and less room for collective action, contestation and representation.

People like Adrian Vermeule and a small number of others want the right to take up the administrative state, not just burn it all down, as seems to be MAGA's agenda. And Lyons'.

But you say anti-managerialism from the right is just replacing one managerialism with another. But take for example all the lost USAID jobs which enmeshed American agendas into the developing world. What is replacing them?